The horror – the stuff that wicker men are made of – comes in the reaction of the villagers:

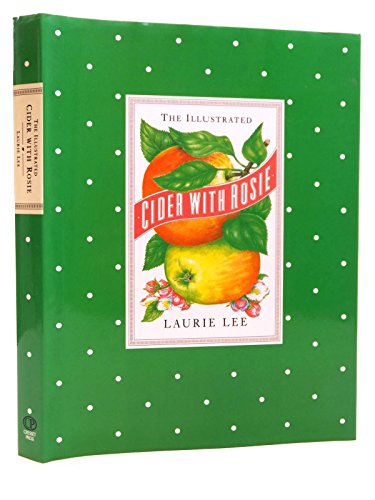

Flashing his money, boasting and insulting the locals, he makes himself the target for a gang which beats him, steals his wallet, and leaves him to die in a snowdrift. In it, Lee tells the story of a traveller, a local boy made good, who returns to the village for Christmas. I didn’t actually think of folk horror until almost half way through the book and a chapter entitled ‘Public Death, Private Murder’. Or, at least at first glance there is, now I know to look for it, something sinister in Roger Coleman’s illustration for the early 1970s Penguin edition I read – a touch of Don’t Torture a Duckling, the uncanny gaze of a child too knowing. Early evening ITV, yellow filters and the gentle romance of rural life.Įvery edition I’ve ever encountered, including the hundred or so dusty copies in the store cupboard at my secondary school, has a cover design signalling that kind of lightness. Silent, savage, with a Russian look, he lived with his sister Nancy, who had borne him over the course of years five children of remarkable beauty.īefore I get to the murder, drowning, haunting, near-death experiences and rape, let me set out what I expected from this book: The Darling Buds of May, I think. John-Jack spent his time by the Bulls Cross signpost staring gloomily into Wales. It is thrown into a run-through of various village characters: The first moment when it occurred to me that I might have the wrong idea about Laurie Lee’s autobiographical novel of life in rural Gloucestershire between the wars was a casual, almost approving mention of incest.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)